|

MAZES

AND HOW TO THREAD THEM.

"In wandering mazes lost."

Paradise Lost.

The Old English word "maze," signifying a labyrinth, probably comes from the

Scandinavian, but its origin is somewhat uncertain. The late Professor Skeat

thought that the substantive was derived from the verb, and as in old times to

be mazed or amazed was to be "lost in thought," the transition to a maze in

whose tortuous windings we are lost is natural and easy.

The word "labyrinth" is derived from a Greek word signifying the passages of

a mine. The ancient mines of Greece and elsewhere inspired fear and awe on

account of their darkness and the danger of getting lost in their intricate

passages. Legend was afterwards built round these mazes. The most familiar

instance is the labyrinth made by Dædalus in Crete for King Minos. In the centre

was placed the Minotaur, and no one who entered could find his way out again,

but became the prey of the monster. Seven youths and seven maidens were sent

regularly by the Athenians, and were duly devoured, until Theseus slew the

monster and escaped from the maze by aid of the clue of thread provided by

Ariadne; which accounts for our using to-day the expression "threading a

maze."

The various forms of construction of mazes include complicated ranges of

caverns, architectural labyrinths, or sepulchral buildings, tortuous devices

indicated by coloured marbles and tiled pavements, winding paths cut in the

turf, and topiary mazes formed by clipped hedges. As a matter of fact, they may

be said to have descended to us in precisely this order of variety.

Mazes were used as ornaments on the state robes of Christian emperors before

the ninth century, and were soon adopted in the decoration of cathedrals and

other churches. The original idea was doubtless to employ them as symbols of the

complicated folds of sin by which man is surrounded. They began to abound in the

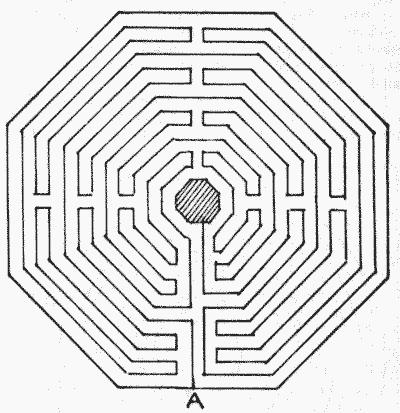

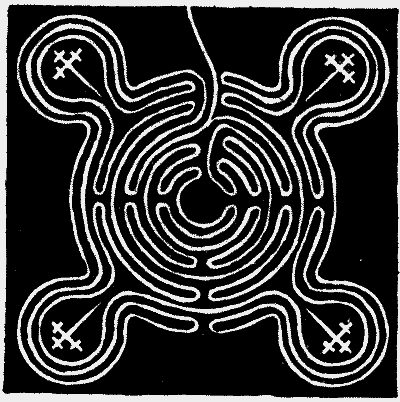

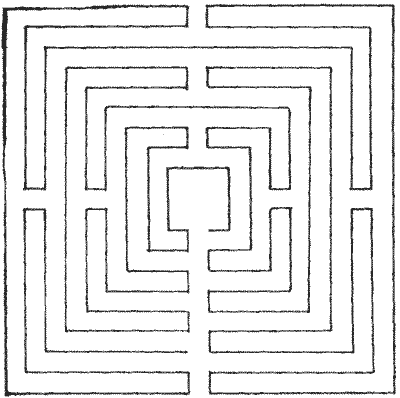

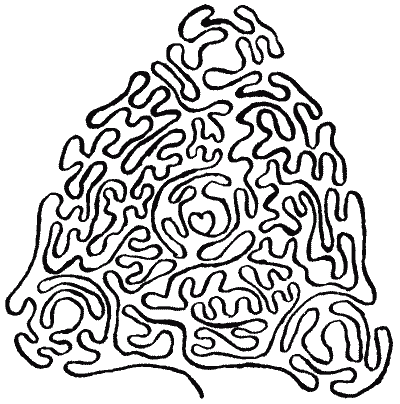

early part of the twelfth century, and I give an illustration of one of this

period in the parish church at St. Quentin (Fig. 1). It formed a pavement of the

nave, and its diameter is 34½ feet. The path here is the line itself. If you

place your pencil at the point A and ignore the enclosing line, the line leads

you to the centre by a long route over the entire area; but you never have any

option as to direction during your course. As we shall find in similar cases,

these early ecclesiastical mazes were generally not of a puzzle nature, but

simply long, winding paths that took you over practically all the ground

enclosed.

FIG. 1.—Maze at St. Quentin. FIG. 1.—Maze at St. Quentin.

In the abbey church of St. Berlin, at St. Omer, is another of these curious

floors, representing the Temple of Jerusalem, with stations for pilgrims. These

mazes were actually visited and traversed by them as a compromise for not going

to the Holy Land in fulfilment of a vow. They were also used as a means of

penance, the penitent frequently being directed to go the whole course of the

maze on hands and knees.

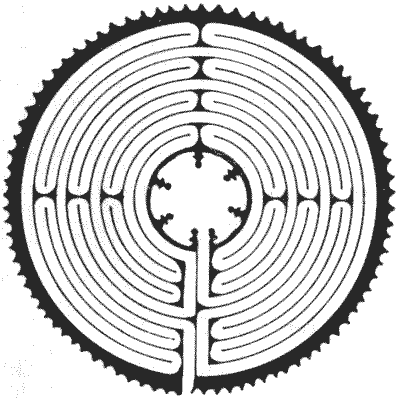

FIG. 2.—Maze in Chartres Cathedral. FIG. 2.—Maze in Chartres Cathedral.

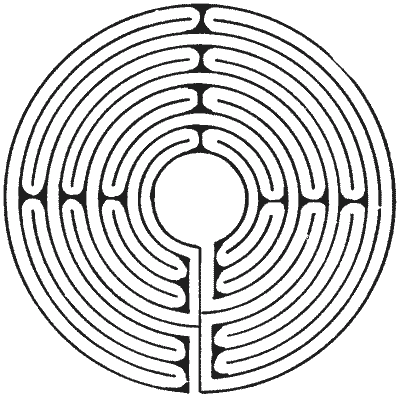

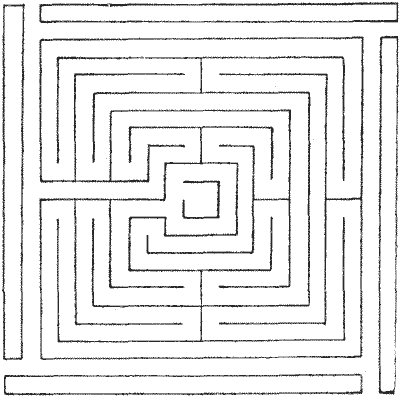

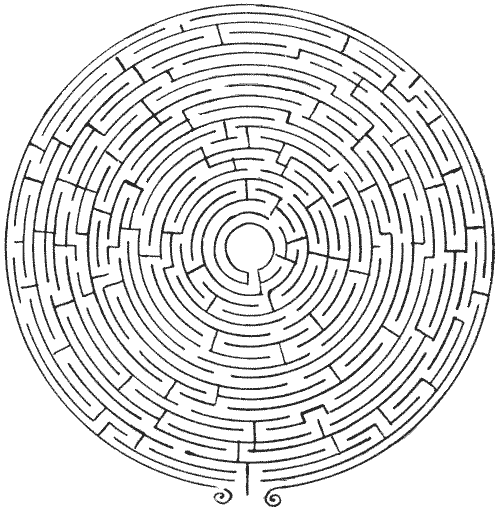

The maze in Chartres Cathedral, of which I give an illustration (Fig. 2), is

40 feet across, and was used by penitents following the procession of Calvary. A

labyrinth in Amiens Cathedral was octagonal, similar to that at St. Quentin,

measuring 42 feet across. It bore the date 1288, but was destroyed in 1708. In

the chapter-house at Bayeux is a labyrinth formed of tiles, red, black, and

encaustic, with a pattern of brown and yellow. Dr. Ducarel, in his "Tour

through Part of Normandy" (printed in 1767), mentions the floor of the great

guard-chamber in the abbey of St. Stephen, at Caen, "the middle whereof

represents a maze or labyrinth about 10 feet diameter, and so artfully contrived

that, were we to suppose a man following all the intricate meanders of its

volutes, he could not travel less than a mile before he got from one end to the

other."

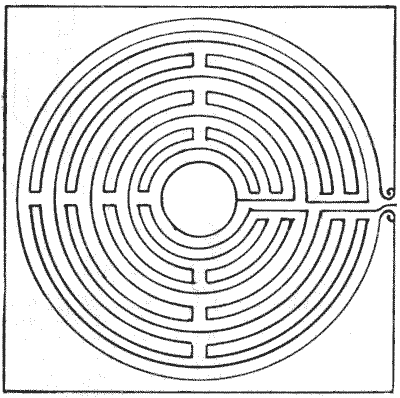

FIG. 3.—Maze in Lucca Cathedral. FIG. 3.—Maze in Lucca Cathedral.

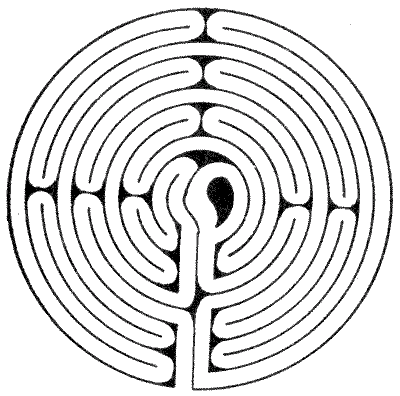

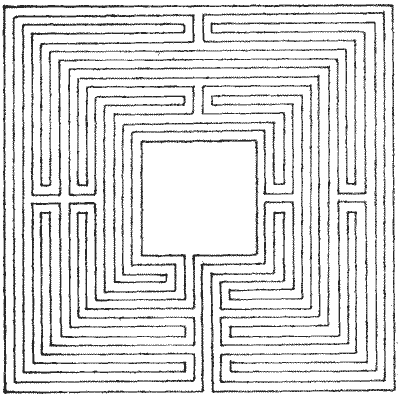

Then these mazes were sometimes reduced in size and represented on a single

tile (Fig. 3). I give an example from Lucca Cathedral. It is on one of the porch

piers, and is 19½ inches in diameter. A writer in 1858 says that, "from the

continual attrition it has received from thousands of tracing fingers, a central

group of Theseus and the Minotaur has now been very nearly effaced." Other

examples were, and perhaps still are, to be found in the Abbey of Toussarts, at

Châlons-sur-Marne, in the very ancient church of St. Michele at Pavia, at Aix in

Provence, in the cathedrals of Poitiers, Rheims, and Arras, in the church of

Santa Maria in Aquiro in Rome, in San Vitale at Ravenna, in the Roman mosaic

pavement found at Salzburg, and elsewhere. These mazes were sometimes called

"Chemins de Jerusalem," as being emblematical of the difficulties attending a

journey to the earthly Jerusalem and of those encountered by the Christian

before he can reach the heavenly Jerusalem—where the centre was frequently

called "Ciel."

Common as these mazes were upon the Continent, it is probable that no example

is to be found in any English church; at least I am not aware of the existence

of any. But almost every county has, or has had, its specimens of mazes cut in the

turf. Though these are frequently known as "miz-mazes" or "mize-mazes," it is

not uncommon to find them locally called "Troy-towns," "shepherds' races," or

"Julian's Bowers"—names that are misleading, as suggesting a false origin. From

the facts alone that many of these English turf mazes are clearly copied from

those in the Continental churches, and practically all are found close to some

ecclesiastical building or near the site of an ancient one, we may regard it as

certain that they were of church origin and not invented by the shepherds or

other rustics. And curiously enough, these turf mazes are apparently unknown on

the Continent. They are distinctly mentioned by Shakespeare:—

"The nine men's morris is filled up with

mud,

And the quaint mazes in the wanton

green

For lack of tread are

undistinguishable."

A Midsummer Night's Dream, ii.

1.

"My old bones ache: here's a maze trod

indeed,

Through forth-rights and

meanders!"

The Tempest, iii.

3.

There was such a maze at Comberton, in Cambridgeshire, and another, locally

called the "miz-maze," at Leigh, in Dorset. The latter was on the highest part

of a field on the top of a hill, a quarter of a mile from the village, and was

slightly hollow in the middle and enclosed by a bank about 3 feet high. It was

circular, and was thirty paces in diameter. In 1868 the turf had grown over the

little trenches, and it was then impossible to trace the paths of the maze. The

Comberton one was at the same date believed to be perfect, but whether either or

both have now disappeared I cannot say. Nor have I been able to verify the

existence or non-existence of the other examples of which I am able to give

illustrations. I shall therefore write of them all in the past tense, retaining

the hope that some are still preserved.

FIG. 4.—Maze at Saffron Walden, Essex. FIG. 4.—Maze at Saffron Walden, Essex.

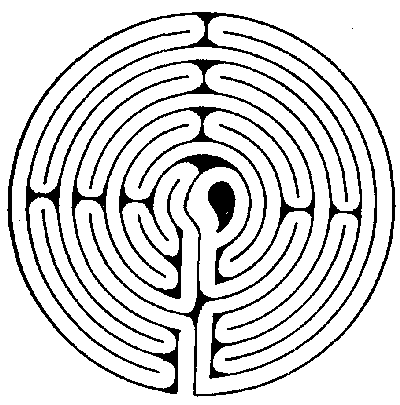

In the next two mazes given—that at Saffron Walden, Essex (110 feet in

diameter, Fig. 4), and the one near St. Anne's Well, at Sneinton,

Nottinghamshire (Fig. 5), which was ploughed up on February 27th, 1797 (51 feet

in diameter, with a path 535 yards long)—the paths must in each case be

understood to be on the lines, black or white, as the case may be.

FIG. 5.—Maze at Sneinton, Nottinghamshire. FIG. 5.—Maze at Sneinton, Nottinghamshire.

FIG. 6.—Maze at Alkborough, Lincolnshire. FIG. 6.—Maze at Alkborough, Lincolnshire.

I give in Fig. 6 a maze that was at Alkborough, Lincolnshire, overlooking the

Humber. This was 44 feet in diameter, and the resemblance between it and the mazes at Chartres

and Lucca (Figs. 2 and 3) will be at once perceived. A maze at Boughton Green,

in Nottinghamshire, a place celebrated at one time for its fair (Fig. 7), was 37

feet in diameter. I also include the plan (Fig. 8) of one that used to be on the

outskirts of the village of Wing, near Uppingham, Rutlandshire. This maze was 40

feet in diameter.

FIG. 7.—Maze at Boughton Green,

Nottinghamshire. FIG. 7.—Maze at Boughton Green,

Nottinghamshire.

FIG. 8.—Maze at Wing, Rutlandshire. FIG. 8.—Maze at Wing, Rutlandshire.

FIG. 9.—Maze on St. Catherine's Hill,

Winchester. FIG. 9.—Maze on St. Catherine's Hill,

Winchester.

The maze that was on St. Catherine's Hill, Winchester, in the parish of

Chilcombe, was a poor specimen (Fig. 9), since, as will be seen, there was one

short direct route to the centre, unless, as in Fig. 10 again, the path is the

line itself from end to end. This maze was 86 feet square, cut in the turf, and

was locally known as the "Mize-maze." It became very indistinct about 1858, and

was then recut by the Warden of Winchester, with the aid of a plan possessed by

a lady living in the neighbourhood.

FIG. 10.—Maze on Ripon Common. FIG. 10.—Maze on Ripon Common.

A maze formerly existed on Ripon Common, in Yorkshire (Fig. 10). It was

ploughed up in 1827, but its plan was fortunately preserved. This example was 20

yards in diameter, and its path is said to have been 407 yards long.

FIG. 11.—Maze at Theobalds, Hertfordshire. FIG. 11.—Maze at Theobalds, Hertfordshire.

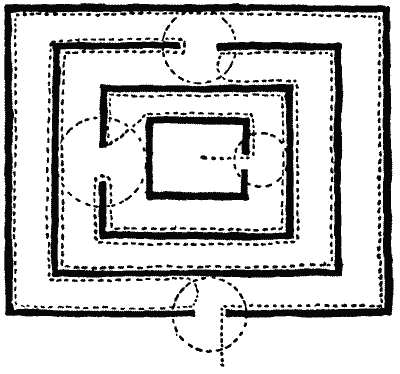

In the case of the maze at Theobalds, Hertfordshire, after you have found the

entrance within the four enclosing hedges, the path is forced (Fig. 11). As further

illustrations of this class of maze, I give one taken from an Italian work on

architecture by Serlio, published in 1537 (Fig. 12), and one by London and Wise,

the designers of the Hampton Court maze, from their book, The Retired

Gard'ner, published in 1706 (Fig. 13). Also, I add a Dutch maze (Fig.

14).

FIG. 12.—Italian Maze of Sixteenth

Century. FIG. 12.—Italian Maze of Sixteenth

Century.

FIG. 13.—By the Designers of Hampton Court

Maze. FIG. 13.—By the Designers of Hampton Court

Maze.

FIG. 14.—A Dutch Maze. FIG. 14.—A Dutch Maze.

So far our mazes have been of historical interest, but they have presented no

difficulty in threading. After the Reformation period we find mazes converted

into mediums for recreation, and they generally consisted of labyrinthine paths

enclosed by thick and carefully trimmed hedges. These topiary hedges were known

to the Romans, with whom the topiarius was the ornamental gardener. This

type of maze has of late years degenerated into the seaside "Puzzle Gardens.

Teas, sixpence, including admission to the Maze." The Hampton Court Maze,

sometimes called the "Wilderness," at the royal palace, was designed, as I have

said, by London and Wise for William III., who had a liking for such things

(Fig. 15). I have before me some three or four versions of it, all slightly

different from one another; but the plan I select is taken from an old

guide-book to the palace, and therefore ought to be trustworthy. The meaning of

the dotted lines, etc., will be explained later on.

FIG. 15.—Maze at Hampton Court Palace. FIG. 15.—Maze at Hampton Court Palace.

FIG. 16.—Maze at Hatfield House, Herts. FIG. 16.—Maze at Hatfield House, Herts.

The maze at Hatfield House (Fig. 16), the seat of the Marquis of Salisbury,

like so many labyrinths, is not difficult on paper; but both this and the Hampton

Court Maze may prove very puzzling to actually thread without knowing the plan.

One reason is that one is so apt to go down the same blind alleys over and over

again, if one proceeds without method. The maze planned by the desire of the

Prince Consort for the Royal Horticultural Society's Gardens at South Kensington

was allowed to go to ruin, and was then destroyed—no great loss, for it was a

feeble thing. It will be seen that there were three entrances from the outside

(Fig. 17), but the way to the centre is very easy to discover. I include a

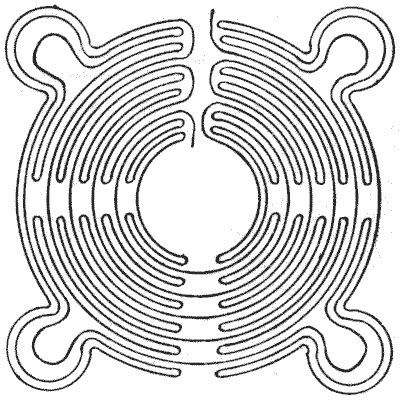

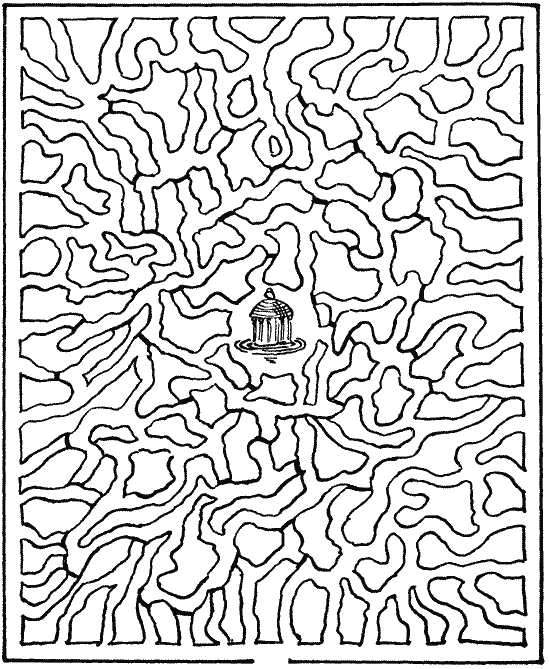

German maze that is curious, but not difficult to thread on paper (Fig. 18). The

example of a labyrinth formerly existing at Pimperne, in Dorset, is in a class

by itself (Fig. 19). It was formed of small ridges about a foot high, and

covered nearly an acre of ground; but it was, unfortunately, ploughed up

in 1730.

FIG. 17.—Maze formerly at South

Kensington. FIG. 17.—Maze formerly at South

Kensington.

FIG. 18.—A German Maze. FIG. 18.—A German Maze.

FIG. 19.—Maze at Pimperne, Dorset. FIG. 19.—Maze at Pimperne, Dorset.

We will now pass to the interesting subject of how to thread any maze. While

being necessarily brief, I will try to make the matter clear to readers who have

no knowledge of mathematics. And first of all we will assume that we are trying

to enter a maze (that is, get to the "centre") of which we have no plan and

about which we know nothing. The first rule is this: If a maze has no parts of

its hedges detached from the rest, then if we always keep in touch with the

hedge with the right hand (or always touch it with the left), going down to the

stop in every blind alley and coming back on the other side, we shall pass

through every part of the maze and make our exit where we went in. Therefore we

must at one time or another enter the centre, and every alley will be traversed

twice.

Now look at the Hampton Court plan. Follow, say to the right, the path

indicated by the dotted line, and what I have said is clearly correct if

we obliterate the two detached parts, or "islands," situated on each side of the

star. But as these islands are there, you cannot by this method traverse every

part of the maze; and if it had been so planned that the "centre" was, like the

star, between the two islands, you would never pass through the "centre" at all.

A glance at the Hatfield maze will show that there are three of these detached

hedges or islands at the centre, so this method will never take you to the

"centre" of that one. But the rule will at least always bring you safely out

again unless you blunder in the following way. Suppose, when you were going in

the direction of the arrow in the Hampton Court Maze, that you could not

distinctly see the turning at the bottom, that you imagined you were in a blind

alley and, to save time, crossed at once to the opposite hedge, then you would

go round and round that U-shaped island with your right hand still always on the

hedge—for ever after!

This blunder happened to me a few years ago in a little maze on the isle of

Caldy, South Wales. I knew the maze was a small one, but after a very long walk

I was amazed to find that I did not either reach the "centre" or get out again.

So I threw a piece of paper on the ground, and soon came round to it; from which

I knew that I had blundered over a supposed blind alley and was going round and

round an island. Crossing to the opposite hedge and using more care, I was

quickly at the centre and out again. Now, if I had made a similar mistake at

Hampton Court, and discovered the error when at the star, I should merely have

passed from one island to another! And if I had again discovered that I was on a

detached part, I might with ill luck have recrossed to the first island again!

We thus see that this "touching the hedge" method should always bring us safely

out of a maze that we have entered; it may happen to take us through the

"centre," and if we miss the centre we shall know there must be islands. But it

has to be done

with a little care, and in no case can we be sure that we have traversed every

alley or that there are no detached parts.

FIG. 20.—M. Tremaux's Method of Solution. FIG. 20.—M. Tremaux's Method of Solution.

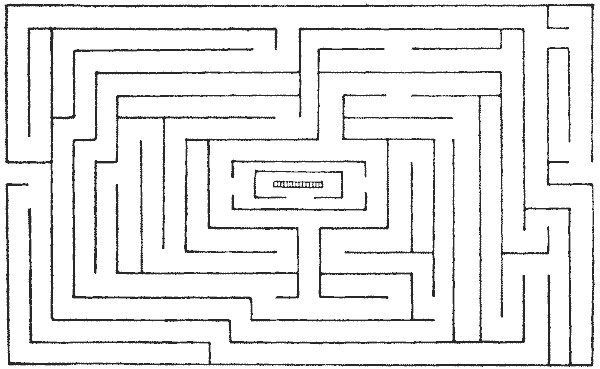

If the maze has many islands, the traversing of the whole of it may be a

matter of considerable difficulty. Here is a method for solving any maze, due to

M. Trémaux, but it necessitates carefully marking in some way your entrances and

exits where the galleries fork. I give a diagram of an imaginary maze of a very

simple character that will serve our purpose just as well as something more

complex (Fig. 20). The circles at the regions where we have a choice of turnings

we may call nodes. A "new" path or node is one that has not been entered before

on the route; an "old" path or node is one that has already been entered, 1. No

path may be traversed more than twice. 2. When you come to a new node, take any

path you like. 3. When by a new path you come to an old node or to the stop of a

blind alley, return by the path you came. 4. When by an old path you come to an

old node, take a new path if there is one; if not, an old path. The route

indicated by the dotted line in the diagram is taken in accordance with these

simple rules, and it will be seen that it leads us to the centre, although the

maze consists of four islands.

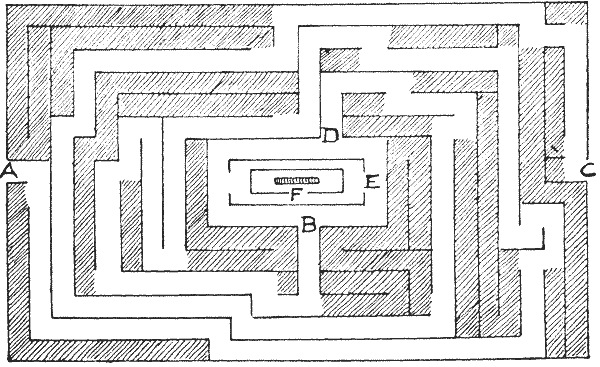

FIG. 21.—How to thread the Hatfield Maze. FIG. 21.—How to thread the Hatfield Maze.

Neither of

the methods I have given will disclose to us the shortest way to the centre, nor

the number of the different routes. But we can easily settle these points with a

plan. Let us take the Hatfield maze (Fig. 21). It will be seen that I have

suppressed all the blind alleys by the shading. I begin at the stop and work

backwards until the path forks. These shaded parts, therefore, can never be

entered without our having to retrace our steps. Then it is very clearly seen

that if we enter at A we must come out at B; if we enter at C we must come out

at D. Then we have merely to determine whether A, B, E, or C, D, E, is the

shorter route. As a matter of fact, it will be found by rough measurement or

calculation that the shortest route to the centre is by way of C, D, E, F.

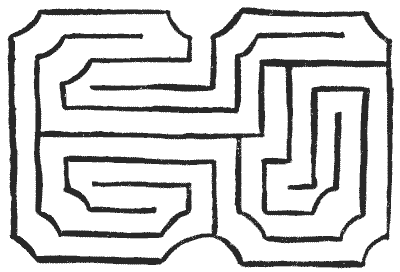

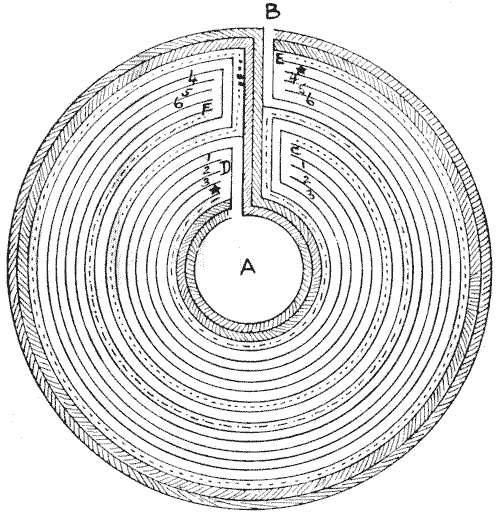

I will now give three mazes that are simply puzzles on paper, for, so far as

I know, they have never been constructed in any other way. The first I will call

the Philadelphia maze (Fig. 22). Fourteen years ago a travelling salesman, living in

Philadelphia, U.S.A., developed a curiously unrestrained passion for puzzles. He

neglected his business, and soon his position was taken from him. His days and

nights were now passed with the subject that fascinated him, and this little

maze seems to have driven him into insanity. He had been puzzling over it for

some time, and finally it sent him mad and caused him to fire a bullet through

his brain. Goodness knows what his difficulties could have been! But there can

be little doubt that he had a disordered mind, and that if this little puzzle

had not caused him to lose his mental balance some other more or less trivial

thing would in time have done so. There is no moral in the story, unless it be

that of the Irish maxim, which applies to every occupation of life as much as to

the solving of puzzles: "Take things aisy; if you can't take them aisy, take

them as aisy as you can." And it is a bad and empirical way of solving any

puzzle—by blowing your brains out.

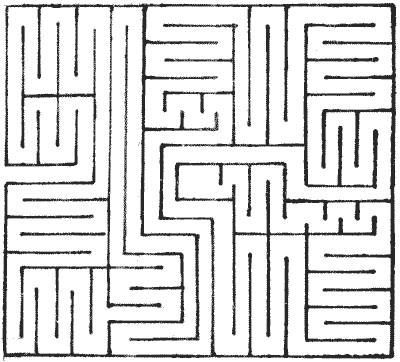

FIG. 22. The Philadelphia Maze, and its

Solution. FIG. 22. The Philadelphia Maze, and its

Solution.

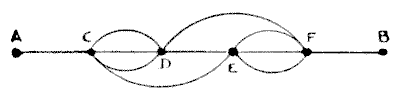

Now, how many different routes are there from A to B in this maze if we must

never in any route go along the same passage twice? The four open spaces where

four passages end are not reckoned as "passages." In the diagram (Fig. 22) it

will be seen that I have again suppressed the blind alleys. It will be found

that, in any case, we must go from A to C, and also from F to B. But when we

have arrived at C there are three ways, marked 1, 2, 3, of getting to D.

Similarly, when we get to E there are three ways, marked 4, 5, 6, of getting to

F. We have also the dotted route from C to E, the other dotted route from D to

F, and the passage from D to E, indicated by stars. We can, therefore, express

the position of affairs by the little diagram annexed (Fig. 23). Here every

condition of route exactly corresponds to that in the circular maze, only it is

much less confusing to the eye. Now, the number of routes, under the conditions,

from A to B on this simplified diagram is 640, and that is the required answer

to the maze puzzle.

FIG. 23.—Simplified Diagram of Fig. 22. FIG. 23.—Simplified Diagram of Fig. 22.

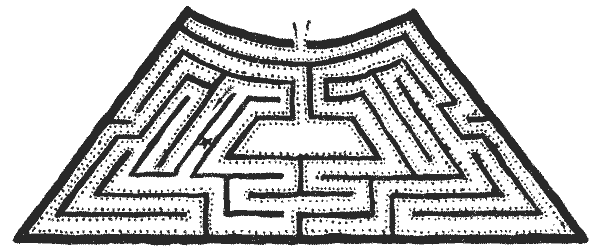

FIG. 24.—Can you find the Shortest Way to

Centre? FIG. 24.—Can you find the Shortest Way to

Centre?

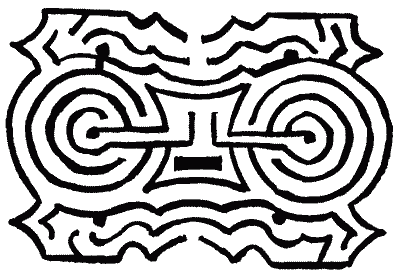

Finally, I will leave two easy maze puzzles (Figs. 24, 25) for my readers to

solve for themselves. The puzzle in each case is to find the shortest possible

route to the centre. Everybody knows the story of Fair Rosamund and the

Woodstock maze. What the maze was like or whether it ever existed except in

imagination is not known, many writers believing that it was simply a

badly-constructed house with a large number of confusing rooms and passages. At

any rate, my sketch lacks the authority of the other mazes in this article. My

"Rosamund's Bower" is simply designed to show that where you have the plan

before you it often happens that the easiest way to find a route into a maze is

by working backwards and first finding a way out.

FIG. 25.—Rosamund's Bower. FIG. 25.—Rosamund's Bower.

Previous Next

|