|

DIGITAL

PUZZLES.

"Nine worthies were they

called."

DRYDEN: The Flower and the

Leaf.

I give these puzzles, dealing with the nine digits, a class to themselves,

because I have always thought that they deserve more consideration than they

usually receive. Beyond the mere trick of "casting out nines," very little seems

to be generally known of the laws involved in these problems, and yet an

acquaintance with the properties of the digits often supplies, among other uses,

a certain number of arithmetical checks that are of real value in the saving of

labour. Let me give just one example—the first that occurs to me.

If the reader were required to determine whether or not 15,763,530,163,289 is

a square number, how would he proceed? If the number had ended with a 2, 3, 7,

or 8 in the digits place, of course he would know that it could not be a square,

but there is nothing in its apparent form to prevent its being one. I suspect

that in such a case he would set to work, with a sigh or a groan, at the

laborious task of extracting the square root. Yet if he had given a little

attention to the study of the digital properties of numbers, he would settle the

question in this simple way. The sum of the digits is 59, the sum of which is

14, the sum of which is 5 (which I call the "digital root"), and therefore I

know that the number cannot be a square, and for this reason. The digital root

of successive square numbers from 1 upwards is always 1, 4, 7, or 9, and can

never be anything else. In fact, the series, 1, 4, 9, 7, 7, 9, 4, 1, 9, is

repeated into infinity. The analogous series for triangular numbers is 1, 3, 6,

1, 6, 3, 1, 9, 9. So here we have a similar negative check, for a number cannot

be triangular (that is, (n²+n)/2) if its digital root be 2, 4, 5, 7, or 8.

76.—THE

BARREL OF BEER.

A man bought an odd lot of wine in barrels and one barrel containing beer.

These are shown in the illustration, marked with the number of gallons that each

barrel contained. He sold a quantity of the wine to one man and twice the

quantity to another, but kept the beer to himself. The puzzle is to point out

which barrel contains beer. Can you say which one it is? Of course, the man sold

the barrels just as he bought them, without manipulating in any way the

contents.

Solution

77.—DIGITS

AND SQUARES.

It will be seen in the diagram that we have so arranged the nine digits in a

square that the number in the second row is twice that in the first row, and the

number in the bottom row three times that in the top row. There are three other

ways of arranging the digits so as to produce the same result. Can you find

them?

Solution

78.—ODD

AND EVEN DIGITS.

The odd digits, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, add up 25, while the even figures, 2, 4,

6, and 8, only add up 20. Arrange these figures so that the odd ones and the

even ones add up alike. Complex and improper fractions and recurring decimals

are not allowed.

Solution

79—THE

LOCKERS PUZZLE.

A man had in his office three cupboards, each containing nine lockers, as

shown in the diagram. He told his clerk to place a different one-figure number

on each locker of cupboard A, and to do the same in the case of B, and of C. As

we are here allowed to call nought a digit, and he was not prohibited from using

nought as a number, he clearly had the option of omitting any one of ten digits

from each cupboard.

Now, the employer did not say the lockers were to be numbered in any

numerical order, and he was surprised to find, when the work was done, that the

figures had apparently been mixed up indiscriminately. Calling upon his clerk

for an explanation, the eccentric lad stated that the notion had occurred to him

so to arrange the figures that in each case they formed a simple addition sum,

the two upper rows of figures producing the sum in the lowest row. But the most

surprising point was this: that he had so arranged them that the addition in A

gave the smallest possible sum, that the addition in C gave the largest possible

sum, and that all the nine digits in the three totals were different. The puzzle

is to show how this could be done. No decimals are allowed and the nought may

not appear in the hundreds place.

Solution

80.—THE

THREE GROUPS.

There appeared in "Nouvelles Annales de Mathématiques" the following puzzle

as a modification of one of my "Canterbury Puzzles." Arrange the nine digits in

three groups of two, three, and four digits, so that the first two numbers when

multiplied together make the third. Thus, 12 × 483 = 5,796.

I now also propose to include the cases where there are one, four, and four

digits, such as 4 × 1,738 = 6,952. Can you find all the

possible solutions in both cases?

Solution

81.—THE

NINE COUNTERS.

I have nine counters, each bearing one of the nine digits, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,

7, 8 and 9. I arranged them on the table in two groups, as shown in the

illustration, so as to form two multiplication sums, and found that both sums

gave the same product. You will find that 158 multiplied by 23 is 3,634, and

that 79 multiplied by 46 is also 3,634. Now, the puzzle I propose is to

rearrange the counters so as to get as large a product as possible. What is the

best way of placing them? Remember both groups must multiply to the same amount,

and there must be three counters multiplied by two in one case, and two

multiplied by two counters in the other, just as at present.

Solution

82.—THE

TEN COUNTERS.

In this case we use the nought in addition to the 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

The puzzle is, as in the last case, so to arrange the ten counters that the

products of the two multiplications shall be the same, and you may here have one

or more figures in the multiplier, as you choose. The above is a very easy feat;

but it is also required to find the two arrangements giving pairs of the highest

and lowest products possible. Of course every counter must be used, and the

cipher may not be placed to the left of a row of figures where it would have no

effect. Vulgar fractions or decimals are not allowed.

Solution

83.—DIGITAL

MULTIPLICATION.

Here is another entertaining problem with the nine digits, the nought being

excluded. Using each figure once, and only once, we can form two multiplication

sums that have the same product, and this may be done in many ways. For example,

7x658 and 14x329 contain all the digits once, and the product in each case is

the same—4,606. Now, it will be seen that the sum of the digits in the product

is 16, which is neither the highest nor the lowest sum so obtainable. Can you

find the solution of the problem that gives the lowest possible sum of digits in

the common product? Also that which gives the highest possible sum?

Solution

84.—THE

PIERROT'S PUZZLE.

The Pierrot in the illustration is standing in a posture that represents the

sign of multiplication. He is indicating the peculiar fact that 15 multiplied by

93 produces exactly the same figures (1,395), differently arranged. The puzzle

is to take any four digits you like (all different) and similarly arrange them

so that the number formed on one side of the Pierrot when multiplied by the

number on the other side shall produce the same figures. There are very few ways

of doing it, and I shall give all the cases possible. Can you find them all? You

are allowed to put two figures on each side of the Pierrot as in the example

shown, or to place a single figure on one side and three figures on the other.

If we only used three digits instead of four, the only possible ways are these:

3 multiplied by 51 equals 153, and 6 multiplied by 21 equals 126.

Solution

85.—THE

CAB NUMBERS.

A London policeman one night saw two cabs drive off in opposite directions

under suspicious circumstances. This officer was a particularly careful and

wide-awake man, and he took out his pocket-book to make an entry of the numbers

of the cabs, but discovered that he had lost his pencil. Luckily, however, he

found a small piece of chalk, with which he marked the two numbers on the

gateway of a wharf close by. When he returned to the same spot on his beat he

stood and looked again at the numbers, and noticed this peculiarity, that all

the nine digits (no nought) were used and that no figure was repeated, but that

if he multiplied the two numbers together they again produced the nine digits,

all once, and once only. When one of the clerks arrived at the wharf in the

early morning, he observed the chalk marks and carefully rubbed them out. As the

policeman could not remember them, certain mathematicians were then consulted as

to whether there was any known method for discovering all the pairs of numbers

that have the peculiarity that the officer had noticed; but they knew of none.

The investigation, however, was interesting, and the following question out of

many was proposed: What two numbers, containing together all the nine digits,

will, when multiplied together, produce another number (the highest

possible) containing also all the nine digits? The nought is not allowed

anywhere.

Solution

86.—QUEER

MULTIPLICATION.

If I multiply 51,249,876 by 3 (thus using all the nine digits once, and once

only), I get 153,749,628 (which again contains all the nine digits once).

Similarly, if I multiply 16,583,742 by 9 the result is 149,253,678, where in each case all

the nine digits are used. Now, take 6 as your multiplier and try to arrange the

remaining eight digits so as to produce by multiplication a number containing

all nine once, and once only. You will find it far from easy, but it can be

done.

Solution

87.—THE

NUMBER CHECKS PUZZLE.

Where a large number of workmen are employed on a building it is customary to

provide every man with a little disc bearing his number. These are hung on a

board by the men as they arrive, and serve as a check on punctuality. Now, I

once noticed a foreman remove a number of these checks from his board and place

them on a split-ring which he carried in his pocket. This at once gave me the

idea for a good puzzle. In fact, I will confide to my readers that this is just

how ideas for puzzles arise. You cannot really create an idea: it happens—and

you have to be on the alert to seize it when it does so happen.

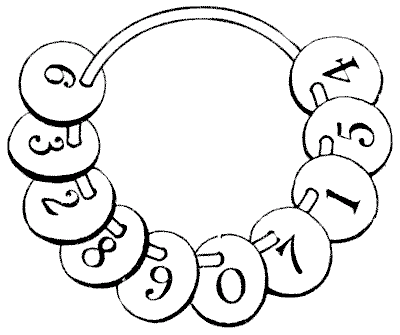

It will be seen from the illustration that there are ten of these checks on a

ring, numbered 1 to 9 and 0. The puzzle is to divide them into three groups

without taking any off the ring, so that the first group multiplied by the

second makes the third group. For example, we can divide them into the three

groups, 2—8 9 7—1 5 4 6 3, by bringing the 6 and the 3 round to the 4, but

unfortunately the first two when multiplied together do not make the third. Can

you separate them correctly? Of course you may have as many of the checks as you

like in any group. The puzzle calls for some ingenuity, unless you have the luck

to hit on the answer by chance.

Solution

88.—DIGITAL

DIVISION.

It is another good puzzle so to arrange the nine digits (the nought excluded)

into two groups so that one group when divided by the other produces a given

number without remainder. For example, 1 3 4 5 8 divided by 6 7 2 9 gives 2. Can

the reader find similar arrangements producing 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9

respectively? Also, can he find the pairs of smallest possible numbers in each

case? Thus, 1 4 6 5 8 divided by 7 3 2 9 is just as correct for 2 as the other

example we have given, but the numbers are higher.

Solution

89.—ADDING

THE DIGITS.

If I write the sum of money, £987, 5s. 4½d.., and add up the

digits, they sum to 36. No digit has thus been used a second time in the amount

or addition. This is the largest amount possible under the conditions. Now find

the smallest possible amount, pounds, shillings, pence, and farthings being all

represented. You need not use more of the nine digits than you choose, but no

digit may be repeated throughout. The nought is not allowed.

Solution

90.—THE

CENTURY PUZZLE.

Can you write 100 in the form of a mixed number, using all the nine digits

once, and only once? The late distinguished French mathematician, Edouard Lucas,

found seven different ways of doing it, and expressed his doubts as to there

being any other ways. As a matter of fact there are just eleven ways and no

more. Here is one of them, 91 5742/638. Nine of the other

ways have similarly two figures in the integral part of the number, but the

eleventh expression has only one figure there. Can the reader find this last

form?

Solution

91.—MORE

MIXED FRACTIONS.

When I first published my solution to the last puzzle, I was led to attempt

the expression of all numbers in turn up to 100 by a mixed fraction containing

all the nine digits. Here are twelve numbers for the reader to try his hand at:

13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 20, 27, 36, 40, 69, 72, 94. Use every one of the nine digits

once, and only once, in every case.

Solution

92.—DIGITAL

SQUARE NUMBERS.

Here are the nine digits so arranged that they form four square numbers: 9,

81, 324, 576. Now, can you put them all together so as to form a single square

number—(I) the smallest possible, and (II) the largest possible?

Solution

93.—THE

MYSTIC ELEVEN.

Can you find the largest possible number containing any nine of the ten

digits (calling nought a digit) that can be divided by 11 without a remainder?

Can you also find the smallest possible number produced in the same way that is

divisible by 11? Here is an example, where the digit 5 has been omitted:

896743012. This number contains nine of the digits and is divisible by 11, but

it is neither the largest nor the smallest number that will work.

Solution

94.—THE

DIGITAL CENTURY.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 = 100.

It is required to place arithmetical signs between the nine figures so that

they shall equal 100. Of course, you must not alter the present numerical

arrangement of the figures. Can you give a correct solution that employs (1) the

fewest possible signs, and (2) the fewest possible separate strokes or dots of

the pen? That is, it is necessary to use as few signs as possible, and those

signs should be of the simplest form. The signs of addition and multiplication

(+ and ×) will thus count as two strokes, the sign of subtraction (-) as one

stroke, the sign of division (÷) as three, and so on.

Solution

95.—THE

FOUR SEVENS.

In the illustration Professor Rackbrane is seen demonstrating one of the

little posers with which he is accustomed to entertain his class. He believes

that by taking his pupils off the beaten tracks he is the better able to secure

their attention, and to induce original and ingenious methods of thought. He

has, it will be seen, just shown how four 5's may be written with simple

arithmetical signs so as to represent 100. Every juvenile reader will see at a

glance that his example is quite correct. Now, what he wants you to do is this:

Arrange four 7's (neither more nor less) with arithmetical signs so that they

shall represent 100. If he had said we were to use four 9's we might at once

have written 999/9, but the four 7's call for rather more

ingenuity. Can you discover the little trick?

Solution

96.—THE

DICE NUMBERS.

I have a set of four dice, not marked with spots in the ordinary way, but

with Arabic figures, as shown in the illustration. Each die, of course, bears

the numbers 1 to 6. When put together they will form a good many, different

numbers. As represented they make the number 1246. Now, if I make all the

different four-figure numbers that are possible with these dice (never putting

the same figure more than once in any number), what will they all add up to? You

are allowed to turn the 6 upside down, so as to represent a 9. I do not ask, or

expect, the reader to go to all the labour of writing out the full list of

numbers and then adding them up. Life is not long enough for such wasted energy.

Can you get at the answer in any other way?

Solution

Previous Next

|